Sagebrush & Summits: Week 1

Boulder, CO to Jackson, WY

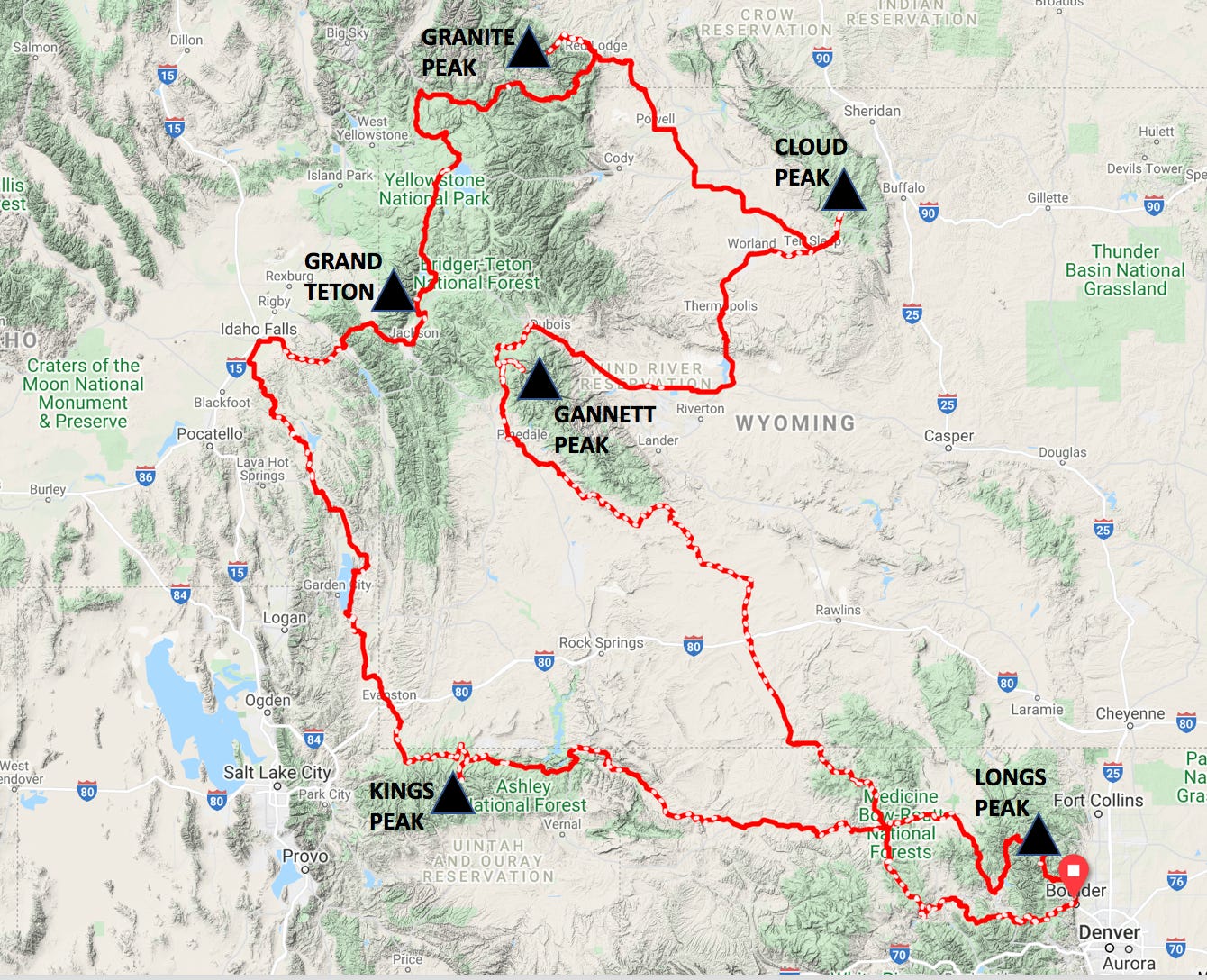

In July 2021 I completed a solo, self-supported 2,300-mile, 21-day bike/run/climb tour through Utah, Idaho, Wyoming, Montana and Colorado. Shortly after the trip, I responded to a lengthy Q+A for Bicycle Quarterly and wrote a cursory summation of the mountain running aspect of the trip for the La Sportiva Blog. However, it was an impactful journey—indeed, the longest bike tour I’ve completed, solo or otherwise—and neither of those pieces came at a time where I had yet been able to fully reflect on the experience. True perspective is often only gained with appropriate distance; two and a half years later, I plan to write about the trip in depth, in three installments—one for each week. The first week took me from my home in Boulder, CO to Jackson, WY, by way of Utah and Idaho.

July 6, 2021: The climb out of Boulder on Magnolia Road is cloudy and cool. An atypical summertime inversion has coalesced overnight and pedaling up Mags’ legendarily steep east-facing gradients I am grateful for the cloudy reprieve from Boulder’s usual blazing summer morning sun. My bike is heavy. Nearly 50lbs before food and water. Fortunately, I’ve always found that after the first few opening miles, your bike weight just is what it is. That hackneyed tautology usually makes my eyes roll, but I think its subtext is actually important---there are some things that, at a certain point, are beyond our control. Stating them as such is a reminder to accept them and move on; don’t waste emotional energy worrying about it.

The 3000’ grunt up into the foothills passes easily. I’m giddily surfing a wave of starting-the-adventure excitement. Although a bit apprehensive, I even record a series of videos outlining my plan for the next three weeks: ride my bike in a 2,300-mile, solo, self-supported loop from my home in Boulder, linking together six iconic Rocky Mountain summits that I will run and climb along the way.

Kings Peak (13,528’)--Uintah Range, Utah’s high point.

Grand Teton (13,751’)--grand monarch of the Teton Range, in northern Wyoming.

Granite Peak (12,807’)--Beartooth Range, Montana’s high point.

Cloud Peak (13,164’)--the crown of Wyoming’s Bighorn Range.

Gannett Peak (13,804’)--Wind River Range, Wyoming’s high point.

And finally, Longs Peak (14,259’), the towering sentinel of Colorado’s northern Front Range and the high point of my Boulder home’s Continental Divide skyline.

Speaking into my phone’s camera as I huff and puff up the hill helps cement my commitment to the trip, even before I upload the video clips to social media. More often than I’d like to admit, I can fall prey to letting perfect be the enemy of good enough. Sometimes you have to quit worrying about conditions or lack of preparation or gear choices or any other myriad doubts and fears and just head out into the world and take your best shot. That’s what I am doing here. After 2020, where pandemic uncertainty supplanted any ambition for big, challenging adventures, I am eager to get out there on A Long One. Take some chances. Have things go wrong. Try hard. Put myself in situations where I will need to adapt and make it all work out. So here I am.

Day 1: Boulder to Radium Springs, CO – 135 miles

First things first, gotta get over the Continental Divide. The east side of the Front Range’s Rollins Pass is notoriously chunky but a mercifully shallow railroad-grade. Crossing its 11,677’ crest is both a geographic and psychological rubicon. After more than four hours and 7000’ of climbing I feel I’m escaping the reasonable day-ride radius of Boulder–and the gravitational pull of home–and my mindset can switch into expedition mode. On the road.

As I awkwardly pilot my rigid bike up the unrelenting rubble of Rollins Pass Road, WNYC’s Fresh Air is playing through my earbuds and rock critic Ken Tucker is reviewing three new albums from, shall we say, seasoned artists Tom Jones, Jackson Browne and John Mayer. Tucker poses the question: how does an artist continue to progress and grow while still considering the audience that originally accorded them success? In the moment, it feels to me like a particularly on-the-nose point of inquiry. I’m only a few hours into a planned three-week bike tour. But I’m ostensibly a professional runner, and July is the heart of a mountain ultra runner’s race season. What am I doing?

To be fair, I haven’t run a race in over six years. Repeated, chronic injuries—shin, achilles, knee—have kept me from a starting line, and I’m not sure my body will ever allow me to line up for an ultramarathon again. At least not with the fitness and health needed to perform at the level that I’ve been capable of historically. In a certain way, I feel that this tour is a statement of my intent and interest in prioritizing a different style of adventure and athletic identity. A starkly different style from what has garnered me an appreciably wide audience and a largely self-determined lifestyle as a top-level mountain runner for the past 15 years.

Tucker’s review makes me think about the artists who I have unfairly become frustrated with as their musical aesthetic has evolved. I think we’ve all experienced this––we discover an artist, their work resonates in a profound way, but then the artist shifts and we’re left disappointed. The reflexive suspicion is usually that they have sold out trying to appeal to a larger audience. Often they’ve just changed so much—irrespective of trying to push into the mainstream—that we’re left wishing they would go back to producing the work that made them attractive to us in the first place.

This is unfair. It is, dare I say, dehumanizing. It’s easy to forget that these people we’ve experienced only as abstractions––heroic archetypes onto which we can easily project any characteristic––are, in fact, living, breathing human beings. They have interests and flaws and traits and persuasions far outside the purview of the inevitably one-dimensional cut-out that they occupy in our mind’s eye.

In her 2012 essay Some Notes on Attunement, Zadie Smith explores this exact phenomenon with respect to her relationship with Joni Mitchell’s music. To wit:

“We want our artists to remain as they were when we first loved them. But our artists want to move. Sometimes the battle becomes so violent that a perversion in the artist can occur: these days, Joni Mitchell thinks of herself more as a painter than a singer. She is so allergic to the expectations of her audience that she would rather be a perfectly nice painter than a singer touched by the sublime. That kind of anxiety about audience is often read as contempt, but Mitchell’s restlessness is only the natural side effect of her art-making...Joni Mitchell doesn’t want to live in my dream, stuck as it is in an eternal 1971––her life has its own time. The worst possible thing for an artist is to exist as a feature of somebody else’s epiphany.”

Perhaps similar to Joni Mitchell-as-painter (to be clear, I’m not at all implying that my achievements as an ultrarunner have ever been anywhere near existing on the same plane as Mitchell’s as a singer-songwriter), I am implicitly expressing a lack of regard for the audience that has accorded me any athletic relevancy and currency in the outdoor industry.

But I need a chance at growth, too. Not only is my body obviously rebelling from two decades of nearly one-dimensional focus, but its failings eventually allowed me to realize how hungry my mind had become for new challenges and stimulus. Over the past decade, adventure cycling, climbing and ski touring have all gradually provided that challenge and stimulus in delightful abundance.

I hope that my enthusiasm for these comparatively fresh activities doesn’t scan as contempt for my first love of running, but I do know that whenever an old injury inevitably flares up my attitude towards the activity and the audience that affords me my livelihood can temporarily tend towards derision instead of gratitude. That derision is, I think, a simple by-product of fear—fear that I won’t be able to continue with the sport that has paid my way, literally and existentially, for over 15 years. But fear isn’t a worthy justification.

A lovely bit of gravel and double-track along Crooked and Keyser Creeks connects me from the Fraser Valley over to the Great Divide Mountain Bike Route (GDMBR), just north of Ute Pass. My plan has been to ride this all the way to Steamboat Springs the first day––an ambitious 180-mile push from Boulder––but I rapidly re-learn the old lesson of adjusting expectations. By the time I’m dropping into the Colorado River Canyon at Radium Hot Springs the sun is already setting, and I’m still some 45 miles short of Steamboat.

No matter, on-the-fly adjustments like this are exactly part of the appeal of bike touring for me. Everything I need is on the bike. As long as I can find some public land––or even a sliver of road ditch––camp is wherever I want to make it. Being untethered from rigid timetables, resupply points and cell service is part of the point.

Day 2: Radium to Brown’s Park, 177 miles

I get an early start to make up for missing my first day’s goal; I’m pedaling by 5:30am. This little corner of Colorado is brand new terrain for me, and its freshness is amplified by a pair of black bears rambling across the trail as I blearily spin up an aspen-lined section of two-track. The long Lynx Pass downhill into Steamboat Springs is a joy and I roll into town before 10am, ready for coffee and a second breakfast to power me through what I hope to be the 180mi push I didn’t achieve the day before.

I know this quasi-neurotic adherence to a predetermined schedule probably sounds a bit...uummmm…unnecessary, if not wholly unappealing, to most cyclotourists. As if I’m missing the point. Indeed, as I coast into the southern reaches of Steamboat, I cross paths with probably a dozen loaded riders, all who seem to be conspicuously southbound GDMBR tourists. I’m a bit embarrassed to admit that my ego brain takes some smug satisfaction in my nearly 50 mile total at that point compared to my assumption that they’ve only traveled the five miles from town so far on the day.

What is that? Why do I have thoughts like that? Who am I trying to impress? Why am I even out here? This isn’t a race, not even an individual time trial of any sort. No, the ostensible imperative of the trip is simply to connect these various and far-flung mountain ranges, under my own power. Ultimately, it doesn’t matter how long it takes me to do it. Maybe I am missing the point.

And yet...this capacity for and interest in long days, pushing my personal envelope, going big—it's a core part of my personality and even my identity. I ran my first marathon when I was only 12 years old, simply because I was curious. Same for my first 100-mile foot race a decade later––could I do it? Were my mind and body up for the task? Certainly, in my teens and twenties, a large part of the motivation there was to differentiate myself from what I likely viewed, consciously or unconsciously, as the plebeian philistine masses. Especially when we’re young, I think we all need something in our lives that makes us feel a little bit unique, a little bit special, elevated, maybe even worthy of attention. For me, since age 11, that thing has been running long distances.

I think recognizing and nurturing this dash of individuality within each of us is fundamentally important. It is the foundation of an integrated, self-actualized identity. Ego gets a bad rap. A friend of mine has proclaimed before that, “without ego, nothing would ever get done.” Whether this view is overly cynical or not, I suspect there is at least a kernel of truth in it. The key, it seems to me, is to strategically leverage ego in moments of, say, low motivation, but to ultimately mature and evolve beyond such adolescent narcissism.

The act of constructing my identity around long-distance running has always been a highly fraught, tenuous exercise. My ambitions often exceeded the limitations of my seemingly fragile musculo-skeletal system, and for the two decades that running was my sole focus, I was frequently injured. Stress fractures, tendonitis, every type of overuse failure of the muscles, tendons and connective tissue that one could imagine.

Up until age 32 or so, the wonders of youth had allowed me to heal and bounce back from each transgression relatively quickly. But a late-winter tibial stress fracture in 2015—product of an internationally competitive 80-mile race that traversed the volcanic island of Gran Canaria—finally motivated me to embrace the bicycle. The thought of missing out on the joys of Colorado’s high country summer simply because I couldn’t run was too much to countenance.

After a couple months of pedaling that spring on my Craigslist commuter, a local purveyor of hand-built steel frames offered to set me up with a bike. I chose their dropbar 29er model—still quite a novelty in 2015—and just like that, the extensive network of gravel, dirt, mining chunk and even singletrack above Boulder was opened to me. With it I found a window into a parallel, but entirely new-to-me, universe of outdoor exploration and recreation. Even when bipedal perambulation became possible again in late summer, I was hooked, and cycling stayed a regular part of my routine. I’d finally come to appreciate it intrinsically, not simply as a temporary means of cross-training in between periods of running health.

Leaving Steamboat Springs, I tack northwest, headed for the border with Utah and the Flaming Gorge on the Green River. It is hot. Nearly +100F and brutally exposed. I leave Craig, CO in mid-afternoon with 4L of water and a dozen burritos, uncertain where I will sleep and with the knowledge that my only guaranteed next resupply won’t be until southern Wyoming, two days and nearly 300 miles hence. Out in the baking and desolate desert beyond Maybell, CO with no cell service, I quickly feel like the last man on earth. A total of two cars pass me over the course of a half-dozen hours. I pedal late into the dark, and after 177 miles I finally call it quits and collapse in the ditch.

Day 3: Brown’s Park to Henry’s Fork Trailhead, 116 miles

After a morning of heat-induced worry and stress—I feel vulnerable riding a remote road in nearly +100F temps—sometime in the late afternoon, somewhere in the middle of the Uinta National Forest, something shifts. I endure what feels like hours and hours of gradual uphill climbing before I am finally treated to a ripping downhill past Hooper Lake. The scenery changes from desert to sub-alpine. Impressive and unexpected hogbacks of rock sprout out of the hills. Within the matter of a few minutes my mood switches. I had spent most of the day battening down despair at the violent sun and my slow progress. Now, after just a mile or two of gravity’s assistance I’m reveling in joy, gratitude and even glee.

The swing is surprising but obviously welcome. At the Henry’s Fork Trailhead for Kings Peak just after sunset, I quickly find a tucked away patch of pine needles for my bivy. Happily supping on gas station burritos in the dark, after three days and nearly 430 miles of pedaling, I’m excited to finally go for a run up a mountain the next day.

Day 4: Kings Peak to Evanston, 81 miles

I have a good run on Kings Peak, Utah’s high point at 13,528’. After a couple miles my legs wake up and I’m able to push the FKT for the 24-mile round trip under four hours, lowering the previous time by 16 minutes. Honestly, despite being a state high point, Kings Peak is a relatively obscure and meaningless objective. But what isn’t meaningless is the flow I find negotiating the steep, teetering talus of Kings’ summit slope, nor the reliably familiar stride I hit on the long run back out to the trailhead. What is important is the feeling of taking my best shot given the circumstances, and having my mind and legs respond favorably, no matter what story the digits on the wristwatch ultimately tell.

Soaking my legs in the trailhead creek afterwards, lunching on still more burritos and filtering water for the 80+ miles to get to Evanston, WY that evening, an ominous brown haze rolls into the valley. Quite the contrast to the crystal clear conditions I’d enjoyed on my run in the alpine that morning just an hour or two earlier. Fire season has started.

The next 50 miles of forest service road to reach the highway that will finally deliver me to Evanston are some of the most trying of the entire trip. I would be fine with the relentless up and down, even with the mountain marathon in my legs from that morning. But the surface, my gaaawwwwd; the state of these roads is abominable. Heavy OHV traffic combined with a lack of rain has churned it into a deep, loose, chunky, washboarded dust pit from hell. It takes me more than six hours to cover these 50 miles before I can hum pleasantly on pavement for the final 30 miles into Evanston. I need to get there; I’m down to my last couple handfuls of trail mix and the day’s varied athletic pursuits have exacted a deep caloric tax that demands remittance.

The afternoon pedaling in the Uintas is a valuable—if excruciating—lesson about managing expectations. If I had only expected the road surface to be that slow—or, better yet, expected nothing at all—I think my angst at the tedious nature of the riding would’ve been a little more manageable.

Day 5: Evanston to Montpelier - 107 miles

I wake up in a Rest Area picnic shelter on the outskirts of town. After my late arrival the previous evening, I’m nursing an exercise hangover this morning. However, it’s amazing how much more simple the packing up process feels when performed upon a concrete slab, with a table to hold all my various possessions, instead of exclusively in the dirt. I almost don’t mind the Interstate 80 traffic noise.

A gluttonous Pilot Travel Center breakfast further delays my departure and it’s after 8am by time I’m pedaling northwards on the relatively new Western Wildlands route—a north-south off-road track developed as an alternate to the eminently popular GDMBR, courtesy of the Bikepacking Roots organization.

The day quickly heats up and the smoke has significantly worsened today. I pull over in the early afternoon on the southern shores of Bear Lake for my first sit-down meal of the trip—a burger, fries, salad and milkshake at a lake resort restaurant. Five days in and my metabolism is revved such that it’s a constant battle to stay fueled.

The temperature seems to cool ever-so-slightly— maybe dipping to +95F instead of +100F—as I continue north along the shores of the lake, but then the route heads up into the hills on yet another hideously loose, cobbled-y mess of a road surface. My 2.2” boots feel inadequate—I wish for plus tires. The long steep climb combines with the beating sun and smokey air to crack me, despite my midday milkshake indulgence. It’s not a physiological bonk, but a mental one. I’m tired of working so hard for such slow miles. The hammering sun, apocalyptic smoke and remote backcountry track are—in aggregate—too much. I just want something to be easy. Or at least not so hard. I scan the map in despair, looking for an alternate destination for my day’s efforts. I’m pooped. Intellectually, I know it’s not actually too terribly far to civilization and other humans, but out here on this desolate dusty ridge of sagebrush in the blazing heat the thin veil of comfort and control that humans have imposed on an otherwise indifferent wilderness feels to be in tatters.

It feels like this trip is exploiting the fact that perhaps I’d been coasting for a couple of years. Maybe it was the pandemic, maybe it was being happy in my relationship with Hailey, but it sure feels like it’s been a long time since I’ve been truly challenged in a way that made me question my ability to get the job done.

I bail onto a paved road and pedal into Montpelier, ID where I scavenge an early dinner at a grocery store and retreat to the city park to bivy behind a gazebo, safe from the sprinkler system. The day’s heat, however, is being held stubbornly in the cinder block wall well after sunset and I fall asleep sweating despite cooling off under a nearby water spigot only minutes before.

Day 6: Montpelier to Idaho Falls - 125 miles

I’m working my way down the Blackfoot River on an incredible road; I make a mental note to come back and ride it with Hailey when it’s not +108F. After I drink the 3L of water that I’d filled back in Soda Springs, the river—a few hundred feet below me and a cooling habitat for many a bovine—beckons deliciously in the smoky heat. These modern, compact, lightweight water filters seem like voodoo to me, and though I typically trust my gut health to them, I’m not willing to roll the dice with a waterway that drains such an ag-intensive region and distinctly smells of cow shit. Instead, I keep pedaling and turn up my podcast against the hair dryer headwind.

Patrick of Bikes or Death is interviewing Bobby Wintle in a rambling, whisky-fueled four-hour epic, and Bobby’s legendary enthusiasm and emotional intensity is providing just enough distraction from my task to keep the PMA high. It’s a minor relief to be audience to a stream of consciousness conversation that isn’t just my own inner dialogue.

Eventually, the endlessly undulating gravel road I’m on drops to the river and crosses it. On the other side, I take off my shoes and wade in fully clothed, hoping my wet shorts, shirt, cap and bandana will serve to keep me cool for just a little longer on the bike. Astonishingly, only a few minutes later, the blast furnace conditions have dried everything.

When I finally exit the remote hills and am out on the dead flat Snake River Plain, I pull out my phone and scan for the nearest gas station. An hour in the air conditioning at an Exxon Good 2 Go eating ice cream and chugging Big Gulps revives me enough to charge the last 20 paved miles to downtown Idaho Falls, aided by a glorious tailwind. I’ve been on the road nearly a week and the last few days of heat and smoke have exacted a toll. All I want is a shower, a real bed and some air conditioning. I get just that, and it’s delicious.

Day 7: Idaho Falls to Lupine Meadows, Grand Teton NP - 122 miles

My late-afternoon climb of Teton Pass goes easier than it should. It’s a big climb—and steep at the top—but my pedal-strokes are aided by the excitement of being on familiar terrain. I’ve spent significant time in Jackson Hole and the Teton Range over the past 15 years and I’ve ridden this pass before.

My mood is further boosted by the undeniable performance-enhancing properties of pavement. The morning’s miles included a couple hours of gravel, but the overwhelming balance of the day’s pedaling has been on tarmac. The increased efficiency is such a relief and a much-needed bolstering of my morale.

As I roll into the outskirts of town I’m enveloped by the familiar hustle and bustle of a summertime National Park gateway town. I feel like I’ve spent so much of the past week toiling away in blistering sun on dusty, lonesome backroads that not only am I unperturbed by the traffic, I almost welcome it. I tap through my phone, scanning for a bike shop, and coast into the open doorway of The Hub, 10 minutes before closing. Nine hundred miles into the trip and with all the gravel and grit of the past week I’m due a new chain (I didn’t start with a fresh one). I know that Jackson is likely one of only two or three places on my route where I’ll be able to source one compatible with my 12 speed cassette.

Next up, Whole Foods. The only one of the whole dang tour. I head to the salad bar and load up on fresh greens and veggies, nutrients that have been sorely absent from my diet so far. I spring for a slab of salmon and some decadent chocolate peanut butter bars to top it all off.

Even though I’ve already covered over 100 miles on the day, I still need to pedal another 20 miles or so out to the national park so I can sleep at the Lupine Meadows Trailhead, launching point for my ascent of the Grand Teton the next day. The sun is setting behind the absolutely spectacular range as I approach the park and I ride the final few miles in near-darkness.

Just before turning onto the gravel road that leads to the trailhead, a car pulls over and a young couple get out. They’ve been following along with my journey on social media and just want to say hello. The beauty and familiarity of the region combined with my satisfying and productive stops in town have me in an expansive headspace of gratitude. I come away from our brief chat touched by their thoughtfulness and interest in what so far has felt like a profoundly solitary pursuit.

But more than that, after a full week on the road, I think I’m finally finding some rhythm and equanimity. Pre-conceptions of time and distance have gradually relented to the week’s repeated beatings, leaving my disposition battered but also in a state more akin to surrender than submission. Basically, come what may, from here on out, I’m open to it.

But also: I get to run up the Grand Teton in the morning! I sleep like the dead.

Thank god you started this! RTW is so back!

As a follower of the old blog, I'm psyched to see you writing longer stuff again.

A question - how do you go about getting this stuff out of your head and onto paper on long stuff like this? I often have all kinds of thoughts that I mean to write down on just a 2-3 hour run, only to have forgotten more than half by the time I'm done. Do you stop to jot down notes mid-ride? Journal a bit at the end of each day? Record audio notes while riding or running? I'd love to hear what sort of system you have for turning on-the-bike thoughts into longer pieces like this. In any event, thanks for sharing as much as you do!